Quentin Tarantino Has a Point About Superman in Kill Bill Vol. 2

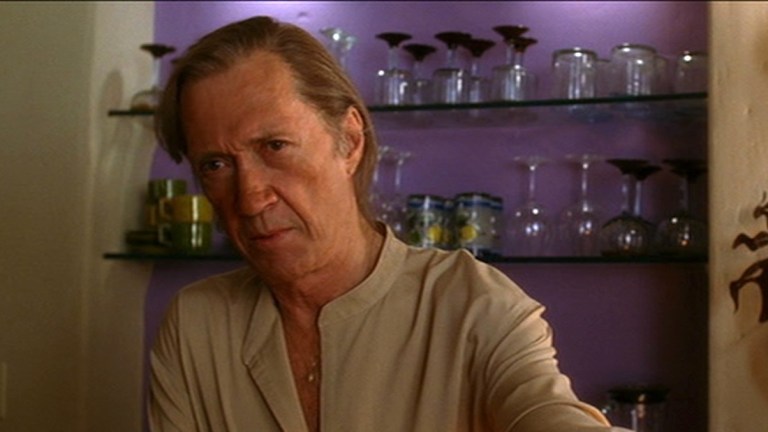

The Superman thesis by David Carradine’s Bill (and Quentin Tarantino) stirred controversy with fans 20 years ago. But maybe we shouldn’t kill the messenger.

Twenty years ago, Kill Bill: Vol. 2 made quite the splash when it reached theaters. Quentin Tarantino movies always do. Some folks basked in its trenchant, loquacious splendor, marveling at how the most grandiose and blood-soaked depiction of vengeance yet in a QT joint could ultimately boil down to a custody dispute between two parents sitting across a table. Others criticized its grittier, more intimate concerns as a letdown following the severed-head glory of Kill Bill: Vol 1… and, finally, there were even those who simply couldn’t get over that amusingly cynical thesis about Superman which the titular Bill drops right before the end of the flick.

If you don’t recall, the scene comes after David Carradine’s antagonist tranquilized Beatrix Kiddo, aka the Bride (Uma Thurman), with enough drugs to force her to listen to a long conversation. But then in Tarantino movies, they’re all long conversations. In this particular instance, Bill wishes to make a point about how his ex-lover could never settle into a “normal” life in rural Texas. And he stresses it by way of pop culture analogy.

“A staple of the superhero mythology is there’s a superhero and his alter-ego,” Bill begins. “Batman is actually Bruce Wayne; Spider-Man is actually Peter Parker. When that character wakes up in the morning, he’s Peter Parker. He has to put on a costume to become Spider-Man. And it is in that characteristic that Superman stands alone.”

He continues, “Superman didn’t become Superman. Superman was born Superman. When Superman wakes up in the morning, he’s Superman. His alter-ego is Clark Kent… what Kent wears, the glasses, the business suit, that’s the costume. That’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us, and what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak, he’s unsure of himself, he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race.”

For a particular type of nerd back in 2004, this spiel was instantly sacrilegious. An act of comic book heresy which dared profane Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s shining beacon of Truth, Justice, and the American Way! QT seemed to be saying… Superman is making fun of us?!?!

I was taken back to these anecdotal comic fan debates, and really the whole arc of superheroes in pop culture, when recently revisiting both volumes of Kill Bill for their 20th anniversary. There has admittedly always been something overtly contemptuous about Bill’s monologue; it drips with the kind of devil’s advocate sneer one might associate with an edge-lord who sought to justify loving literature created for children—or in another decade down the road, someone eager to defend why Zack Snyder’s Superman so callously kills enemies when he isn’t posing like Christ. One might even say Bill’s (mis)interpretation of Superman, a character designed to radiate hope to kids, is the kind of thinking that got us a scene of Henry Cavill in a red cape moping, “No one stays good in this world.”

And yet, with a couple decades of perspective, there’s a case to be made that Superman’s use of a secret identity, as well as most superheroes in comic books, is in fact some form of commentary on the culture they reflect. I’d stop short of saying Superman is criticizing humans as purely weak or cowardly (even that reading of Clark Kent as a performative dorky disguise only applies to Christopher Reeve’s version of the Clark/Superman dichotomy). However, Superman and many of the costumed do-gooders who followed in his wake are depicted time and again as having good reason to hide their faces from the world (or at least beneath a pair of glasses).

While Superman was hardly the first fictional hero to be depicted with a secret identity—that honor probably belongs to Zorro, who was created nearly 20 years before Action Comics #1—the Man of Steel was the one who set the template for the comic book superhero genre that would define the medium for the rest of the century. By day, Superman is a mild mannered reporter for The Daily Planet, a seemingly pleasant but unremarkable man who hides his greatness.

Obviously, this was intended to be a power fantasy for young children, and that would be heightened by comicdom’s blossoming stable of heroes for the rest of the golden age: Batman, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, etc. would fight crime by one alias, and live their daily lives by another, often while winking at the reader when Lois Lane wonders why Clark Kent always misses Superman, or Commissioner Gordon shrugs off Bruce Wayne as an oblivious socialite.

Within their fictional worlds, there is a method to this duplicity. If their enemies knew their real names, their loved ones would be in danger. However, as the genre matured and deepened in the following decades, the reality that the characters and their various guiding writers and artists kept returning to is that the biggest danger was as much from the public themselves. They had reason to fear their villains… and you too.

While the Green Goblin knowing who Spider-Man is turned out bad for Gwen Stacy in a famous 1970s comic book, Peter Parker’s life on the page never unraveled worse than in the One More Day storyline, where after choosing to unmask himself to the public, Parker is estranged and sued by his former employer and friends at The Daily Bugle, has one ex-girlfriend betray him to bounty hunters (Liz Allan) and another drag his name through the tabloid press by writing a tell-all book (Debra Whitman). Frankly, all of these developments air closer to character assassination in keeping with that entire period of bad decisions in the Spider-Man comics under Joe Quesada’s editorial leadership. Still, the larger point remained: if Spider-Man is unmasked everyone will betray him—and do nothing to help once the Kingpin puts out a hit that leaves an elderly old woman mortally wounded.

This lesson seems to apply to most old-school superheroes. When Daredevil was unmasked to the public during a Brian Michael Bendis run in the 2000s, he became paparazzi and New York Post fodder in his hometown (a fate worse than death) and was legally brutalized by his enemies like the Kingpin; Nightwing is arrested when he was bizarrely unmasked in late 2010s comics; and then of course Alan Moore and Curt Swan’s iconic swan song for the original golden age Superman, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? ends with Superman forced to create a whole new secret identity after his Clark Kent alias is blown, and sure enough supervillains come out of the woodwork to kill his ex Lana Lang, his best friend Jimmy Olsen, and even his dog Krypto.

The underlying subtext of comics’ reliance on the secret identity trope is that humans by our very nature are naturally dangerous, untrustworthy… and maybe weak. And the only way to live a happy life is to deceive those around you. At its core, the concept of a “secret identity” is both a power fantasy and a recipe for emotional angst. Stan Lee made a mint by embracing the downsides of living a double life and being torn at the seams in those earliest Spider-Man comics, which featured Peter Parker quitting the tights more than once. Yet time and again, comics justify the necessity to wear a mask, or to hide from oneself in public, because the public is dangerous.

If Superman was sent to Earth to guide us to a better future, which is how most fans and talents like to perceive the character (even Zack Snyder), he inherently seems to have a strong reason to still never trust those he’s leading to the promised land—after all, the most famous messiah in Western storytelling was crucified.

By extension the entire medium of superhero fiction could be seen as a vaguely misanthropic metaphor for the need to control: be it through the physical power of our proverbial watchmen or through information—which is carefully curated, controlled, and censored for us. One might even say the Clark Kent construction envisioned by Bill/Tarantino became a journalist specifically to help shape public opinion about a man running around with an “S” on his chest.

At its essence, traditional superhero fiction casts a wary eye toward its fellow man, and it’s a gaze Tarantino just happened to pick up on.