Little Richard: I Am Everything Reveals a Sometimes Reluctant Rock Pioneer

Director Lisa Cortés reframes the blueprints from the architect of rock and roll in Little Richard: I Am Everything.

Nobody has bragging rights like Little Richard Wayne Penniman. The “Architect of Rock and Roll” torched the blueprints of blues and gospel music with the cleansing fire of the dirty lyrics and burning piano licks. He struck the match to fire up James Brown’s Famous Flames, taught Paul McCartney to scream, and global teens to rip it up on the dance floor. The Beatles opened for him. Little Richard was also a triumphant force for civil rights, and a reluctant pioneer in sexual identity. A new documentary claims the title Little Richard: I Am Everything, so “shut up,” as he would say so often it became a revolutionary catchphrase.

With that title, director Lisa Cortés sets a daunting task, not only does she have to prove the claim but be extremely entertaining while doing it. Little Richard was, after all, one of the most electrifying performers to hit a stage. For the most part, the documentary achieves both ends, though it would have benefitted so much from more vintage live performances. Archival interview clips bring glimpses of the unpredictable magnetism of the rock and roll icon in person. As a character study, Cortés presents a completely engaging contradictory lead figure. But her aim is also to educate, expanding the scope of Richard’s achievements and vision, but bending under the combined weight of inclusivity. There is a lot to unpack.

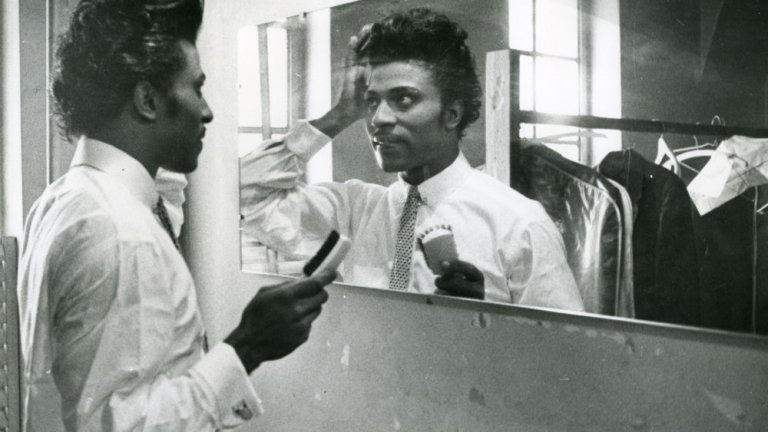

The film strips the whitewash from early rock and roll to give it a rainbow finish, with Black at the very center. Little Richard was an outlier. His race, sexuality, and deep religious commitment didn’t fit into the accepted narrative of early rock and roll. Using family photos and archive stills, Cortés expertly evokes both Richard’s childhood, and the landscape, inner and out. “The south is the home of all things queer,” scholar Zandria Robinson says in the film, “of the different, the non-normative, the other side, the gothic, the grotesque. Queerness is not about sexuality, but a presence in a space that is different than what we expect, different from the norm.”

Born in 1932 in Macon, Georgia, Richard was one of 12 children. His father was a church deacon who ran moonshine and operated a nightclub, but could not deal with an effeminate son, kicking Richard out of the house at 15. The young piano playing singer relocated to a local speakeasy, which was also an unofficial gay bar. The documentary makes it feel like Little Richard found a home, not just because he was taken in, but embraced by the performing arts and artists on the fringes of entertainment and society.

No one was expecting Little Richard to shake things up the way he did. But the documentary shows he was learning from the best. He was still a teenager when Sister Rosetta Tharpe brought him out on stage while he was working at the Macon City Auditorium. Tharpe’s “Strange Things Happening Every Day” is one of the songs accompanying the sequence, subliminally augmenting the multiple lessons Little Richard was learning.

The segment on Little Richard’s influences is particularly fascinating for some of the songs the documentary digs up. While raunchy lyrics can be heard in many old blues songs, even the commentators in the documentary proclaim Lucille Bogan’s “Shave ‘em Dry” to be surprisingly offensive. It is comforting to know a song from 1937 can still shock a young listener. While the song is merely straightforward in its frank sexual presentation, it makes Little Richard’s original lyrics to “Tutti Frutti” sound romantic, which it is. Cleaned up by Dorothy Labostrie, the wop-bop-a-loo-bop words were initially a howling endorsement to anal sex. All of this makes for great further comparison when Pat Boone renders the song downright antiseptic. It is still vaguely enraging that his and Elvis Presley’s versions of Little Richard’s songs outsold the originals. The ever-classy Richard, for the most part, is shown to be very publicly grateful for the two white singers lining his pockets with the loose change of residuals, until he realizes how little that really adds up to.

The film takes off during periods of Little Richard’s reclamations of what is his. He may have borrowed the mix of boogie-woogie rhythm with barrelhouse blues melodies from Ike Turner, but Jimi Hendrix? Little Richard honed the legendary guitarist’s craft in the backing band. The once and forever gospel singer Richard also baptized The Beatles. Holding court to their ultimate fanboy proclamations. They were British, they knew royalty, and no rock and roll star was more regal than Little Richard. He wore gowns. He glittered. Cortés breathlessly captures his glow through the excitement of her pacing.

Cortés is a fan. She may not have been when she first started the work on it, but by the film’s end we know she is a believer. Whether Little Richard was making pitches as a snake oil salesman, dragging his piano rolls through the guise of Princess LaVonne with Sugar Foot Sam from Alabam’ on the chitlin circuit, or giving it all up to study theology at Oakwood College, Cortés finds an underlying perspective. Though she sometimes misses spots, like why Richard stopped his academic pursuit, possibly conscious of how Black artists have been historically sidelined by scandalous tidbits.

Also, there are no interviews or anecdotes about Richard’s male lovers. While this is probably because none would step forward, it would have afforded a unique vantage point to the dichotomy at the artist’s sexual center “He was very good at liberating other people through his example,” music historian Jason King explains. “He was not good at liberating himself.”

Little Richard was a liberating force to performer and LGBQT+ activist Sir Lady Java, and legendary burlesque dancer Lee Angel. Both intimate acquaintances give revealing interviews, which continue to hold deep emotional ties to the contradictory man behind the many myths. The documentary shows Little Richard to be unapologetic about his open and orgiastic rock and roll lifestyle policy, telling Joan Rivers in an archival clip, “If you knocked on my door and I wanted more? For sure!” But then dialing it back for God.

Cortés even shows Little Richard’s flamboyant presentation to be a mix of the sacred and profane. Archival interviews find him applauding the stylistic influences openly gay musicians Billy Wright and Esquerita exerted in the early 1940s, from pompadours, makeup, and stage wear, to how to pound those ivories. The film counters this in contemporary talking-head commentary. African American Studies professor Tavia Nyong’o explains how Black ministers could raise the roof just as high during sermons as singers could on the stage. Even Richard’s conversion to born again Christianity is high drama, sparked by an apocalyptic vision the singer had in 1957 on a plane during a tour of Australia. It was the first, but not last time he would renounce secular music.

The documentary also shows Richard knew who he was, what he was doing, and how it reverberated. “I’m not conceited,” he says at one point. “I’m convinced.” Interviews with Nona Hendryx and Tom Jones back up his claims. “I’d never seen any of it before,” Mick Jagger says at one point in the film. “He created the template for the rock and roll icon.” The documentary shows others were not quite so knowledgeable, such as in a clip from the 1988 Grammys telecast, where Richard declares himself the winner, three times, before presenting the award for best new artist. The U.S. Recording Academy never afforded Richard the accolades he deserved, and he was one of the greatest forces in music to break down the walls of racial segregation.

“He spit on every rule there was in music,” cult film director John Waters remembers, going on to point out how “even racists in Baltimore” danced to Richard’s music. Waters’ own pencil mustache is a “twisted tribute” to Little Richard, we learn, as Cortés surreptitiously highlights how diverse the musician’s influences truly are.

Use of cover tunes, such as those sung by Valerie June and John P. Kee during the “Dreamscape Performances,” is novel in a documentary. The performances, sadly, pale in comparison to the original live footage left to our imagination. The film also relies a little too much on talking head interviews, and would have moved better with archive footage along with voice-over commentary. Certain parts of the film feel too scholarly, when we could have heard more from members of Little Richard’s backing band.

Cortés, along with editors Nyneve Minnear and Jake Hostetter follow Little Richard’s chronology, but keep the structure loose. Cortés’ doesn’t hide from Richard’s later years, but excels at showing how the artist became the superstar, and why he deserves so much more than the credit he was denied in life. Little Richard: I Am Everything ends on a montage of all the artists inspired by the self-proclaimed “emancipator,” such as David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, Rick James, Prince, and Harry Styles. If only there were more performance footage of the architect himself.

Little Richard: I Am Everything can be seen in theaters and on demand April 21.