The Best Horror Movies Set in Broad Daylight

Sun’s out, guns out! And knives, ghosts, cannibals, ancient rituals…

Things that go bump in the night, fears of the dark, nights of things like The Demon, The Living Dead, The Hunter and… err… The Lepus (big rabbits), are mainstays in horror. Something half glimpsed in the gloom when everything is quiet and people are sleeping is innately creepy. So it can sometimes be extra special when a horror movie manages to scare the bejesus out of us despite being set in the cold light of day. Or indeed, as is the case with many of the following movies because they are set in broad daylight.

So let the sun warm your skin while our favorite daytime horrors chill your heart!

Midsommar (Ari Aster, 2019)

This is an obvious first pick because part of the gimmick (and we mean that with affection) of the movie is that it’s set in Sweden during a commune’s Midsummer festival where the nights are very short and the days long and bright. Florence Pugh plays Dani, a young woman grieving the horrific deaths of her sister and parents. Dani attends these festivities with her boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor) who had intended to dump her, and several of his friends. There in the harsh light they witness older commune members willingly plummet to their deaths, strange and harrowing ceremonies and a dizzying mix of psychedelic colors, wholesome bonding and an undercurrent of absolute wrong-ness.

Director Ari Aster lets the film bathe in the sunlight with the flowers and trees throbbing with half seen faces, and heart beats of their own. It’s deliberately trippy and unnerving before slamming us with brightly lit atrocities that you can’t shy away from. This was the follow up to his deeply dark and oppressive debut Hereditary – he’s almost turned that film on its head with Midsommar while proving light can be just as horrible as dark.

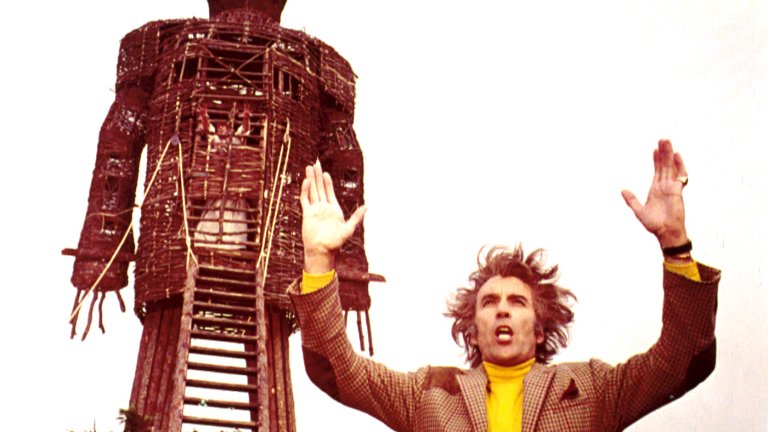

The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973)

Midsommar clearly owes such a debt to Robin Hardy’s classic folk horror, The Wicker Man, that it’s only right the two should sit next to each other. In this 1973 classic highly religious police officer agent Howie (Edward Woodward) travels to the pagan island of Summerisle to investigate reports that a young girl named Rowan has vanished. Howie suspects that the islanders have sacrificed the girl to save their ailing crops but as Howie digs deeper he finds himself led on a merry dance by the islanders.

Like Midsommar, The Wicker Man forces you to question who is right – the uptight Howie or the sexually liberated, nature-worshiping islanders, until the final horrific conclusion. The summer celebrations have reached their colorful, floral, grotesque and sun soaked climax, and only then does Howie really understand the games Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee) and his followers have been playing.

It Follows (David Robert Mitchell, 2014)

While there are certain sequences in It Follows that do indeed take place at night and are very effective, it’s the way the movie makes mundane day time scenes entirely menacing that’s the ace up It Follows’ sleeve. Essentially a film about a sexually transmitted ghost, the threat in It Follows is a shape-shifting entity which will pursue the afflicted person relentlessly at all times, unless they are able to pass the curse on – this is done by having sex with someone, who then has the ghost. If the entity ever catches up to and touches a victim, they die. But if that happens then the curse returns to its previous owner.

It’s a great premise which flips on its head the usual trope that to be alone in the dark is the most dangerous state. In fact, being around lots of people in the daylight is worse – it’s impossible to know if any random stranger approaching is actually the entity.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974)

Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece takes place over one day and night – opening with sun rise over a cemetery where a deformed sculpture which appears to be made up of body parts is strapped to a grave. This is a film that bakes you in the heat of the Texas sun so hard you can smell the rot (and certainly the cast could during the scenes in the house which were riddled with flies). Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns), her brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain) and their friends are visiting the house where they used to live on a hot summer’s day but when they get there it’s adorned with bones and skin. Then they meet Leatherface. Things grow worse as the day progresses until only Sally remains – the final scenes of Leatherface swinging his chain saw wildly in the morning light are iconic.

Old/The Happening/The Village (M. Night Shyamalan, 2021, 2008, 2004)

M. Night Shyamalan has a habit of setting large parts of his movies in daylight so we’ve given you a few to choose from. If you wish to dispute which of these belongs on a “best” list feel free to come at us in the comments – and please note you don’t see Lady in the Water or After Earth on this list despite them also being partially daylight set.

What these three have in common is the importance of the natural world to the plot, and the idea of finding horror in places we’d associate with beauty. Old is set on an idyllic beach. The Happening imagines a world where nature itself is the threat. The Village is (or is it…?) set in an old world commune where everything is perfect, were it not for the monsters. It’s clearly a preoccupation.

Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971)

This nightmarish Aussie movie has several utterly devastating night time scenes (the Kangaroo hunting sequence is probably enough to put animal lovers off watching this film at all), but the relentless heat and dust of “the Yabba”, the town where school teacher John (Gary Bond) stops over on his way to Sydney, is nightmare enough. This is an outback town that John initially looks down on, until he finds himself stuck there after getting drunk and losing all his money in a gambling game.

The dirt and sweat are palpable in this descent into hell which sees John shed his pretensions and his principals in the boiling outback where there’s little to do but drink and fight. This is harrowing stuff, with a particularly memorable turn from Donald Pleasence as Doc, a former physician who has chosen to live outside of society’s norms. Brilliant but deeply upsetting.

Who Can Kill a Child? (Narciso Ibáñez Serrado, 1976)

An English couple on holiday are terrorized by murderous youngsters in this Spanish film from director Narciso Ibáñez Serrado. Tom and his pregnant wife Evelyn visit a beautiful Spanish island before Evelyn gives birth to their third child. When they arrive the island appears to be populated entirely by feral children who work together to terrorize the couple, and appear to be able to recruit other children to their ways just through eye contact. It’s a bleak tale of what could drive a man to, well, kill a child, again juxtaposing the bright, beautiful island and the supposed innocence of kids with extreme acts of organized violence.

Documentary footage at the start of the film shows these are kids who have been affected by wars and violence perpetrated by adults. As such then it’s a cautionary tale: raise a child with the horrors of war and you’ll be bringing up a generation who think that’s normal. And it comes with a nasty kicker – this isn’t going to end with the island either.

Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1978)

When George A. Romero made Night of the Living Dead, he was both innovative and a traditionalist. He more or less invented our modern understanding of what a “zombie” is as it shuffles across the screen. But also apropos of the grainy and cheap black-and-white film stock he used, Night was a classic ghosts and goblins story: there’s something out there in the dark… and it’s coming to get you, Barbara.

Which is one of the many reasons the Dawn of the Dead follow-up is so startling. Like the title promises, the harsh light of day is going to be shed on the idea of a zombie apocalypse. And unlike Night, civilization—complete with all its prejudices and injustices—is not returning. Instead the undead have inherited the earth, and we spend a lot of time with our few surviving characters who have to share the space with them.

As much a dark comedy and satire as it is an exploitative creature feature, the dead, much like the living, descend in hordes on the super-shopping malls of this era. One zombie isn’t scary in passing, but seeing the same shuffling and bumbling corpse day after day roaming the halls of a mall is its own kind of maddening hell. Hence, it stands to reason, eventually gleaning dozens of them, and then hundreds, coming to the mall in the bright light of day, or the high fluorescence of commercial lighting, sends a beleaguering chill down the spine. These things don’t come out mostly at night; in fact, they’re already here with you right now when you go outside.

Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

Jaws’ seminal importance in the annals of Hollywood moviemaking, as well as modern blockbuster cinema, can sometimes obscure the fact that it’s a horror movie… and a damn scary one at that. Despite being rated PG (by ‘70s standards) and set during idyllic summertime days along the New England shore, Jaws is one of the few horror movies credited with changing peoples’ habits, particularly with regard to the beach. To this day, I know grown adults who fear the water because they saw Jaws as a child.

Yes, a large part of that is about the power of suggestion, with Spielberg forced to improvise due to a malfunctioning mechanical shark. Most of the attacks in the first half of the movie are filmed absent a giant fish. Instead we’re merely given the suggestion of the leviathan’s presence by way of an upturned raft; a drifting piece of debris that seems to be hooked on something moving fast; or of course the look of total terror on the face of a young woman before she’s pulled under the surf screaming. Much of the movie is set during the day in middle America’s idea of paradise…. And it makes all that red sea water still run cold.

The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963)

It became a famous anecdote when Alfred Hitchcock explained the notion of suspense to François Truffaut. In a nutshell, he pointed out a scene wherein a bomb suddenly explodes from beneath a table would surprise an audience, but showing the audience (and not the characters) the bomb is there before the scene begins turns it into a sequence of grueling, delicious suspense. Yet maybe the best example of this is one which shows the true perverse genius at work in Hitch’s head: he turns the proverbial bomb into everyday birds.

Throughout 1963’s The Birds, our fowl friends become harbingers of doom and dread when they seem to declare apocalyptic war on mankind for our cruelty to their species. Yet in perhaps the most dreadfully wonderful scene, the audience has already become aware of avian critters’ homicidal instincts. So when Tippi Hedren decides to have a smoke outside a school, waiting for a little girl inside, she is slow to recognize the growing danger as one crow after another gathers on the playground behind her. In the broad afternoon light of day, scored only to the sound of a children’s game inside, as common a sight as a murder of crows nestling in a jungle gym is made nefarious… and we’re forced to wait breathlessly until they go boom. At which point, the fate of Hedren, the children, and a doomed school teacher who cannot save them all is left for the birds.